Year of the fly

Native hover flies dominate the Darwin mango flowering season.

WHY STUDY MANGO POLLINATORS?

Many crops need or benefit from insect pollination. The insects providing pollination services often vary widely between crops, growing regions and even between years. By studying crop pollinators, we may be better able to protect and manage pollination services in the future.

WHAT KINDS OF INSECT VISIT MANGO FLOWERS?

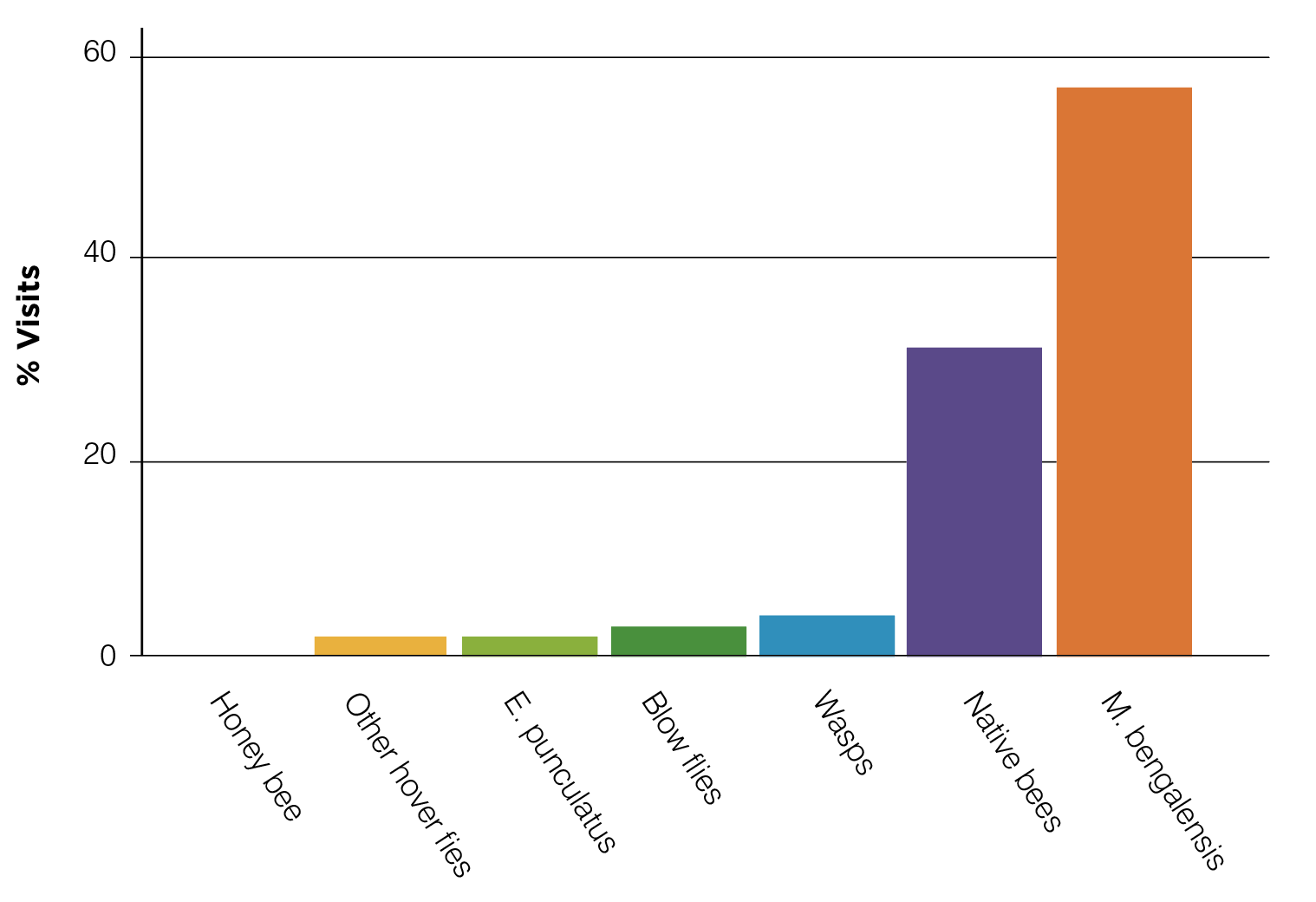

In the flowering season of 2021 (Jun-Jul), we surveyed mango flower visitors on three farms around Berry Springs in the Northern Territory (NT). Surprisingly, flower visitation was dominated by just a single species of native hover fly, Mesembrius bengalensis (Syrphidae). This one species alone accounted for 57% of all visits!

Meanwhile, another native insect, the stingless bee, Tetragonula mellipes (Apidae), made up a further 31% of visits. The remaining 12% of visits were made up by various flies, bees, and wasps, including a second hover fly species, Eristalinus punctulatus (2%).

In contrast, European honeybees accounted for less than 1% of all visits. This is surprising as honeybees often dominate flower visitors in many Australian crops, including apple, cherry, almond and avocado, and are also known as a mango flower visitor in some regions.

Hover flies are an ever-present but generally only small component of pollinator communities worldwide. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time hover flies have been documented as the dominant flower visitor in any crop!

WHY DO FLIES VISIT FLOWERS?

Hover flies are part of the insect Order Diptera, which contains the “true flies”.

The Order Diptera includes many familiar and related flies such as blow flies, fruit flies, march flies and even mosquitoes.

Like bees, many fly species will visit flowers to collect nectar and pollen. They use these resources to power their extremely rapid flight, as well as for developing eggs and sperm for reproduction.

When dissected, the guts of many Mesembrius hover flies that we collected from the mango farms were packed with mango pollen.

Furthermore, the ovaries of many Mesembrius females were full of large eggs. This suggests that the hover flies were actively breeding during mango flowering and using the mango pollen to power their energetic sex lives.

ARE FLIES POLLINATORS?

In short, yes. Flies in general have been well documented to carry and deposit pollen of many plant species. In some cases, hover flies deposit as much pollen as honeybees. However, as hover flies are usually less common than bees, their contribution to pollination is generally thought to be less important.

Although Mesembrius bengalensis was the most abundant flower visitor in our surveys, it is not yet known if this species is an effective pollinator. However, several factors suggest that Mesembrius should be a good pollinator. In pollinators, both larger body sizes and hairiness often correlate with pollination performance. The relatively large size and hairiness of Mesembrius therefore suggest that it is likely to deposit significant amounts of pollen on the stigmas of the flowers it visits.

WHERE DID THE FLIES COME FROM?

The dominance of flies in this mango flowering season comes after a very strong wet season in the NT.

Anecdotally, in previous drier years, such as 2019, these hover flies were much less common.

Although the larval habitat of Mesembrius is unknown, close relatives of these flies typically breed in low oxygen and water-logged habitats, where they feed on bacteria and other microorganisms. Darwin is surrounded by a vast network of wetlands and flood plains that increase in size substantially after “the wet”. We therefore suspect that Mesembrius may breed in these wetlands and their offshoots. The pronounced wet season is likely to have increased the size of these wetlands and may explain the high abundance of hover flies in 2021.

FUTURE RESEARCH?

In the future, we plan to quantify the amount of pollen transferred to stigmas when these flies visit mango flowers, to demonstrate their pollination efficiency. We also hope to confirm our theory on the importance of wetlands and rainfall for populations of Mesembrius. If correct, our research suggests that protecting the wetland habitats around Darwin may be critical to safeguarding pollination services in the future. However, it may also be possible to use our knowledge of the life history of Mesembrius to promote, and possibly supplement, pollinator populations. This may be particularly important in dry years.

Meanwhile, comparing mango pollinator communities in Darwin to those in northern Queensland and Western Australia will allow us to understand if these strategies may also be applied to other tropical growing regions.

We hope that our work will help support pollinators and pollination services in the Australian Mango Industry.

Acknowledgments

The Managing Flies for Crop Pollination project (PH16002) is funded by the Hort Frontiers Pollination Fund, part of the Hort Frontiers strategic partnership initiative developed by Hort Innovation, with co-investment from the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia, The University of WA, Western Sydney University, University of New England, Seed Purity Pty Ltd and Biological Services and contributions from the Australian Government. It has also been funded by Hort Innovation, using the avocado research and development levy and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.

By Dr Jon Finch and Prof. James Cook, Western Sydney University.